Suunto Blog

Watch this underwater drone footage of Will Trubridge diving deep

The X-Adventurer Freetracker is going to be a game changer for freediving.The X-Adventure Freetracker following William down. © Daan Verhoeven

When Suunto ambassador William Trubridge attempts to break his own freediving world record in July, an underwater drone will follow his dive.

He and his team tested the drone, called the X-Adventurer Freetracker, during Vertical Blue 2016 and hope at next year’s competition it will offer live video to audiences around the world.

It’s mounted on parallel tracks adjacent to the competition dive line, and descends and ascends with the diver, capturing the entire journey from the surface to the plate and back again.

See how long you can hold your breath as William dives!

“For this year we just got a proof of concept,” Will says, “but for next year’s Vertical Blue we hope to have it hooked up to a live internet feed, so people can watch from the other side of the world while an athlete grabs the tag at 120 m.”

“I think it’s going to be a real game changer for the sport because once people can tune in and be in their living room watching someone dive to 100 m as it happens, then that will really increase the spectatorship of the sport.”© Daan Verhoeven

Aside from making freediving more accessible to spectators, The X-Adventurer Freetracker will also improve safety. Never before have safety staff been able to see what’s happening for an athlete at depth before. If anything goes wrong, the safety crew will see it immediately via a live feed at the surface.

“It will definitely help with analysis of technique also,” Will says. “Because there's such a logistical difficulty in videographers going deeper than 40 m, a lot of freedivers have never seen what their technique looks like at depth from a good angle.”

William is attempting to break his current world record of 101 m this July and the X-Adventurer Freetracker will follow his journey into the depths.

Stay tuned!

How to use Suunto AIM-6 Thumb Compass

Mårten Boström says that the process of developing a new compass was an interesting one. “I have realized how much I as an elite orienteer can give insight to the product development team into how the product is actually used,” Boström says.

The team came up with an innovative design that supports three methods of direction finding. You can easily switch between methods, even during the same event, to match the challenges of your current terrain or the distance to the next control point.

With the AIM compasses it is possible to find and follow the direction in different ways. Which methods do you use and when?

On short legs I simply place the compass on the control leg and turn my body facing the next control to align the map meridians and needle north.

After I have picked a distinguishable object in the terrain to aim for I check which color/symbol -combination the north arrow is pointing to and aim for that same visual combination on every glimpse while proceeding towards the next control.

If I only need a course direction towards a big object (e.g. a lake) I might just use a whole sector in a similar manner.

On long legs I turn the compass capsule so I can see the north arrow fit in the orienting indicator – thus I don't need to keep the compass on top of the map on the rest of the leg.

In all of these I'm of course AIMing into the correct direction where the red arrow on the far end of the compass plate is.

The new Suunto AIM-6 can be used with a magnifying lens. When do you use that?

A loupe (or magnifying lens) is starting to be a popular accessory even for orienteers with good eyesight. There are more and more details on the maps nowadays and the loupe really helps.

Place the loupe in front of the thumb compass so that you can see the corner of the compass baseplate but mainly magnifying the map.

READ MORE

Learn more about the new AIM-6 and AIM-30 compasses

World champion’s 10 tips for orienteering

Meet the orienteer who runs a 2h 18m marathon

DEVELOPING A NEW ORIENTEERING COMPASS IS A TEAM EFFORT

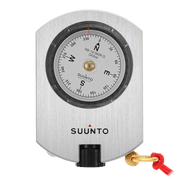

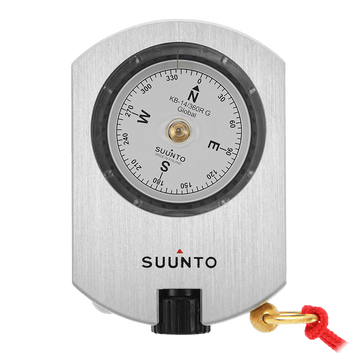

Today we are launching two new orienteering compasses at the Jukola relay in Lappeenranta, Finland. Both the new Suunto AIM-6 thumb compass and the AIM-30 baseplate compass were developed together with Sprint Orienteering World Champion Mårten Boström .

Mårten, when did you start working on this project?

I have been involved in the development of Suunto's new orienteering compass line from the beginning of the year.

Product development is exciting as I have realized how much I as an elite orienteer can give insight to the product development team into how the product is actually used.

Mårten Boström worked closely with Suunto's compass business line manager Henrik Palin and designer Heikki Naulapää.

What did you want to change or improve?

As the compass is an orienteer's most precise aiding tool in navigating it's been an interesting task to refine the current compass to become an even better friend when out in the woods.

I wanted to redesign the needle in order to achieve a better contrast on to the map, make the needle much more stable while keeping it fast and take away some markings on the baseplate.

The graphics on the baseplate and the compass capsule were designed based on Mårten’s feedback.

Since the use of the compass needs to be swift I wanted to add color and symbol codes on the edge of the bezel so that there's no need to rotate the compass capsule. Using the colors and symbols one can simply memorize where the arrow is aiming and advance rapidly.

Our goal was to make the colors and symbols on the AIM distinguishable but easily memorable.

What are the key characteristics of a great compass?

A great compass should be easy to use and have a fast & stable needle.

How do you actually test a compass?

The compass is best tested in actual orienteering conditions out in the forest where temperatures vary from -10°C to +35°C and twigs hit your face while you are trying to navigate through unknown terrain over hills and through marshes!

Learn more about the new AIM-6 Thumb Compass

Learn more about the new AIM-30 Compass

Alex Mustard takes over @SuuntoDive Instagram

Marine biologist, author and pro photographer Alex Mustard is taking over @suuntodive for a week, beginning today. Make sure to catch his incredible images and the stories behind them! What’s your story, Alex? I’m an underwater photographer and marine biologist from the UK. I have been taking underwater photos since I was nine years old and diving since I was 13. I’ve recently distilled all I have learned into the new book Underwater Photography Masterclass. Where do you dive?

All over the world! In salt water or fresh water. In crystal clear blues of the Pacific Ocean to murky green-browns at home in England. What inspires you about the underwater world? The diversity. This can be the biodiversity of life – the ocean is home to such a variety of animals, that getting to know them, watching the different ways they live their lives, is certainly many lifetimes worth. But more than that it’s the diversity of diving experiences I love. One week I might be aiming my lens at a great white, and the next week I am just as excited to be framing up seaslugs back home. Then it is on to shooting in caverns, with cathedral like light beams spilling in through gaps in the ceiling. And next diving deep inside a wreck, searching for secrets that nobody has noticed before.

How would you describe your photography style? I would say diverse. The non-diving world sees me as a specialist underwater photographer, of course. But within underwater photography I challenge myself to be able to photograph everything well, from shipwrecks to seahorses. Is there a story you wish to tell with your images? Most of us who dive are very passionate about the underwater world. Yet we all see how humanity is hurting the oceans. Taking out too many large predators, damaging fragile environments with destructive fishing and polluting the seas. I think that all photographers hope that their images will inspire a change in attitude from the general public.

Follow @SuuntoDive to see Alex’s images or follow him on Instagram and Facebook. Check out his book Underwater Photography Masterclass.

The Old Bullet pushes beyond his comfort zone – and inspires others on the way

Suunto UK has partnered up with the Columbia Threadneedle World Triathlon Leeds in England. Amongst the 5,000 professionals and amateur triathletes competing, there is one that caught our eye – Jim McKellar – who just so happens to be the same age as us. Both Jim and Suunto turned 80 this year! We got in touch and found out a little more about what makes him tick.

As a veteran of 120 marathons and ultras alongside being a member of the Great Britain Age-Group Team at the ITU World Championships, Jim McKellar, or ‘Old Bullet’ as he is known by his running friends after his multiple exploits at the Comrades Marathon in South Africa, is no stranger to pushing the boundaries of our self-imposed limitations. But what makes his achievements particularly impressive is that he only took up running at 51 after being made redundant from his workplace of 25 years.

“I lost my pride and became a bit of a mess,” Jim tells us. “My doctor told me that if I carried on like I was, I’d be dead in five years. So I entered the London Marathon. That was back in 1992.” Twenty consecutive London marathons later, and it’s fair to say he'd got the bug.

You’re never too old to take up triathlon

But it wasn’t until the ripe old age of 74, shortly after completing his 120th marathon, which happened to be the 89 km long Comrades (for the third time), that he took up triathlon and in the following year entered the 2012 Windsor Triathlon, even though he didn’t know how to swim.

“Triathlon training is horrendous,” he laughs, “but I’m getting there”.

The following year, in 2013, he qualified for the ITU World Championship at Hyde Park and competed in the 75–79 age group, coming 3rd in the country and 10th in the world, one of his proudest achievements. He had hoped to return the following year, but it wasn’t meant to be.

Overcoming setbacks

Sadly, not long afterwards Jim suffered a major setback. Out cycling with his club, he was involved in a collision with a car, suffering injuries to his pelvis and a chipped bone in his right leg that required specialist treatment and skin grafts. For 18 months walking was hard enough, let alone running or cycling.

Now, most people under the circumstances might decide to call it quits, but not Jim. Indeed, if ever a man embodied the spirit of Suunto, a determination to win and to never give up, Jim is it.

“I need that challenge of getting up in the morning,” he continues. “My wife had myeloma cancer and for the past three years, I looked after her 24/7. We battled on. I’m battling on now – I will not give up.” Sadly, his wife passed away in March, making him even more resolved to compete in this year’s Columbia Threadneedle World Triathlon Leeds.

However, Leeds won’t be without its challenges if Jim is to achieve his goal of winning gold in his age group (M80-84) as a tribute to his late wife Lily – and in the process raise money for MacMillan. “My leg injuries have curtailed my training a little,” he says with a wry smile. “I’m not bothered about the swim or bike – I’m riding a hundred miles a week – and my swimming’s come on a treat, but I’ve had to adopt a let’s get round job in the run element.”

“Every morning I do exercises up lampposts to get rid of all the stiffness in my leg. But I’m up to six to eight miles of fast walking and jogging, which I’m pleased with considering three months ago I couldn’t go 100 yards.”

And so he should be pleased. Because as Jim points out, people don’t use their full potential and simply compete in their comfort zone. So perhaps we should follow his example, and learn to push ourselves beyond the norm. We never know, we might just surprise ourselves.

Images by James Carnegie

Read more triathlon stories:

10 Ambit3 hacks for triathletes

How to use the power of commitment

7 spring training camp tips for triathletes

7 tips to help you make amazing diving videos

Jill exploring the Bell Island mine. © Cas Dobbin 2016

Today there are no barriers to entry for shooting underwater video. GoPro cameras have put awesome potential within easy reach both physically and financially. Even with this compact camera, 4K video can be shot, edited and uploaded to social media sites. However, with video capability in everyone’s hands, there are some key things you need to do to separate yourself from the pack.

First things first

General diving skills are critical with good buoyancy control being at the top of the list. Master this first!

Watch Jill's video of devil rays off the coast of Azores Islands.

The gear

Shooting underwater means you are filming through a filter. Colour and light are gradually absorbed the deeper you go. In many cases, visibility can be minimal. You need good quality, wide-angle video lights to help illuminate the scene and increase colour saturation. The closer you can get to your subject, the less filtering water between you and a great shot. Use a wide-angle lens for shooting or try macro work with a tripod – only if you can avoid damaging the environment.Watch Jill exploring Devil's Ear cave system, Ginnie Springs.

Shoot for easy editing

Don’t try to edit in the camera. That means you should shoot long sequences with a long “tail” after the action has passed. This gives you room to edit and use transitions.

Slowly, slowly!

Move very slowly and deliberately and consider holding long stationary shots to let the environment and marine life flow around you. Most beginners get overly enthusiastic and move the camera around too much. They are eager to film the next shot rather than patiently working on the current encounter. That type of footage is not just tough to edit but can give your viewers seasickness!Press play to see the shipwrecks of Bell Island.

Capture variety

When you shoot, try to capture a wide range of shot types. You need wide establishing shots that show context. You will want to capture things like jumping off the boat or preparing gear. You'll also need an endless supply of shots called cutaways. These short clips of a few seconds in length are the glue that holds longer shots together. When a diver is prepping gear we might see a cutaway of the pressure gauge needle popping up as the tank is turned on. We might see a quick okay signal close up on a hand. You can never have enough cutaway shots in the edit. You will use every single one you shoot.

Press play to watch Jill talk about her diving career.

Show the tranquillity

Remember, the beauty of the underwater world is best enjoyed drifting along rather than frenetically bouncing around from view to view. Let your shots breathe and allow your viewers to enjoy the same peace and tranquillity that you do on a swim along a perfect reef. The marine life will be more likely to cooperate and gracefully participate in your sequence too.

Keep it short

And finally, when you get into the postproduction phase, keep your edit short. Try to tell a story in less than three minutes. That is about the attention span of most viewers. Nobody wants to see the entire dive and the things you missed. If you only have 90 seconds of great footage, then keep your edit even tighter. You’ll get more hits and shares and enjoy watching your own masterpiece again and again.