Suunto Blog

Three ways to navigate with a Suunto Spartan GPS watch

Jeff Pelletier, a trail runner and filmmaker from Vancouver, BC, Canada put together this great video with some tips for navigating with the Suunto Spartan. He showcases how you can navigate in new surroundings or challenging terrain using these three different features of the Spartan.

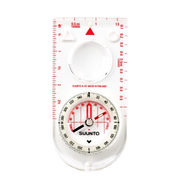

1. Routes

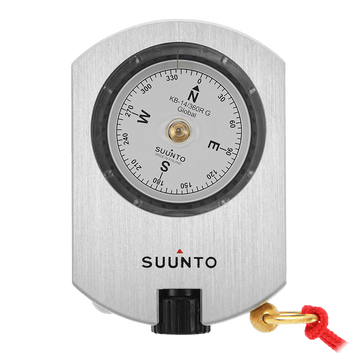

2. Compass

3. Breadcrumb

Watch the video now!

You are not limited to these three ways to navigate. You can also use POI navigation (read how this is done here). In addition, as of the Spartan update in June (1.9.36) you can now also use find back navigation which plots your quickest route back to your starting point utilizing the compass to guide you.

Main image by @jpelletier

Learn more about Suunto Spartan GPS watches

Meet the 21-year-old woman on a six-year running high

I ran my first 100km when I was 16 just one year after I started running

Yep, I went from 0 to 100 in one year at age 16. It’s my dad’s fault. His name is Ashley. It was his second 100k. He’d been running marathons, and once realized he wouldn’t get faster, he decided to go longer. The race was the Surf Coast century.

I’ve run six 100ks since.

And more 50ks than I can even remember. I do them in training – I'll just head out for an afternoon 50. I did three weekends in a row of just 50k runs.

I didn’t love running at the start.

I thought it was hard! Then there I was running a 50k, back to back to back every weekend. It’s amazing what you can do.

But now I’ve been running for six years non-stop.

I started running, and I just did so many easy kilometers with my dad. I built this base very naturally, not forced. Now that I have the base I can do the harder training sessions. I have six years of non-stop running. That’s a big base no matter how old you are.

What I love most is the places I go and the people I meet.

If you didn’t have the people in this sport that were so raw and so organic, it would be a completely different sport. The places you go is really exciting but the people you meet keep you competing.

I want to do the Hard Rock 100

Just because it’s so hard to get into. Transvulcania. And some of that are totally off the grid – ones I don’t even know about, in really cool locations.

I always have a plan, and I never follow it.

I’m pretty reactive and pretty in tune with my body. I’m totally OK with missing a training session or going day by day. I always have a plan but I very rarely follow it. My racing style is not aggressive – I would say I’m someone who eases into it. I start slow and finish strong.

My toughest race? World Sky Running Champs 2016

It was a marathon in Catalonia. I had never seen terrain quite like it. A lot of scree and skiing down scree slopes. I really struggled with it. But I finished the race.

I’m so glad I’m 21...

So I was able to run my last big event: The Marathon du Mont Blanc, 80km of trail in Chamonix. It was the first time I could run the race – because I’m finally 21 years old. But the big goal of the year is the TDS as part of the UTMB weekend.

…but I was a little terrified to start my last race!

I’m a big fish in a small pond in Australia. Now it feels like I’m stepping up to the big leagues. It’s very leveling and I’m a small fish in a big pond – the talent and level is amazing. And more importantly, we just don’t have terrain like this in Australia. I was a bit terrified for my last race! I didn’t have enough time to run every section – only the first climb and last climb, and a few sections in between.

It was 80km.. then 85km… then 92km

The race is called the Marathon du Mont Blanc 80km. They told us the actual course was 85km. Then they modified it to get us more water – but that came with an extra 500m climb and seven more kilometers.

I had a great start, a tough middle section, and strong finish

I felt pretty tired coming into Chamonix, and almost didn’t start the race. The first three hours were great, the next four were terrible, then I hit the halfway point and started counting down the K’s and picking off ladies as I moved up field. I finished in 13h23m, twenty minutes behind 1st place, in a tight battle for 2nd place – I was only a minute ahead of 3rd!

It’s an honor to be a young gun

I know a lot of people are watching me and saying 'maybe it’s safe to start that early.' It’s really exciting to inspire other young runners.

Images by Damien Rosso / Droz Photo

It’s not easy being Emelie! Get in the mind of one half of a mountain-sport power couple

OK, we’ll go ahead and correct ourselves – or at least amend. Whether it’s easy or not, it’s certainly one thing: fun. Emelie Forsberg is a Swedish mountain runner and ski mountaineer, and the better half of Spanish superman Kilian Jornet . Over the last two years, the pair have been running literally around the world – and now, they’re running up it, by heading to the Himalayas for Emelie first high-altitude foray – and a record-setting ascent by Kilian. Here’s how it all went down.

I’ve been to the Himalayas before, but not like this

I’ve been running in the Himalayas plenty, but I’ve never done anything quite this: an attempt on Cho Oyu, an 8000m peak and the sixth tallest mountains in the world.

We did all the acclimatization at home

I was there for less than two weeks – most people take two months to acclimatize. This is very much new-school, fast-and-light alpinism. We did all the acclimatization at home hooked up to a machine that simulated being up at 7500m.

People hear we did an expedition, and they think ‘sherpas’

But that’s not how we did it. That’s not how I want to go the mountains, and not how Kilian wants to go to the mountains.

There was no pressure

This was a trip I did for myself, out of my own pocket – so there was very little pressure to ‘do it for the sponsors’. I wanted to explore for myself and see what was possible for myself.

At sea level Kilian is much faster

But at altitude we start to even out a little bit more – although he will always be stronger and more technical. We were surprised at how fast we were moving at altitude – about 250m an hour at 7500m. That’s pretty fast.

I reach 7500m and 7800m on two different days

The first time was a planned acclimatization. The second attempt was a summit bid – it was our last day, and there was a small weather window. But it got late, bad weather started rolling in, and I simply decided to turn around. Kilian and I discussed that he would go on. I had to wait a few hours for him to come down – during that time I regretted a bit the decision to split up.

Ueli’s death gave us a big scare

We were in Cho Oyu we got the news about Ueli Steck. I didn’t know him personally well, but he was friends with Kilian. He was extreme but he was a hero. His life was an affirmation of everything that is possible. When he died it was hard.

Kilian never considered not following through

There is a big difference between Ueli’s very technical route and Kilian’s Everest Route. I knew Kilian was in a really good shape and responding well to the altitude. I knew he would be fine on Everest in the right conditions. When he was taking longer than expected I began to worry a bit, as Kilian is usually extremely good at predicting his times – but I was getting updates from Seb Montaz.

I don’t want to do Everest

I want to go to some high altitude mountains. I really liked it. Mountains are the foundation, racing is just the topping. I love running and skiing, and I’m fascinated with alpinism, but I’m more concerned about the exposure. I don’t like that. I’m a big fan of life. I don’t see myself moving in the kind of terrain that Ueli did, in the way that he did. Even if I attained the technical skills, I don’t think I want to be here.

I would like to go back to Mt Blanc

Ii have been running up and down many times, but I want to put a record on that one – there’s not so many women doing it. I would like to go back to Cho Oyu to ski, as the winter route looks amazing. Some other bigger peaks as well. But Cho Oyu on skis might be my next dream trip.

I am happy Kilian is done

I want to keep his passport so that he can’t go anywhere for some time!

#howdoirun makes runners stronger

“I was surprised by how well people ran in general, I expected much worse,” says running coach Adam St. Pierre from CTS. Adam and Jason Koop, another CTS coach, have been commenting the running videos.

What were the most common issues you saw in the videos?

“I think the most common issues I saw related to posture. A few people leaned too far forward, bending at the waist, a few people were too straight up (or even leaning back). Proper running mechanics starts with posture. Without good posture it is very difficult to have an effective arm carriage or sufficient hip flexion and extension. If hip flexion is limited, it is very difficult for a runner not to overstride. If hip extension is limited, it puts strain on the lower back and limits the ability of the gluts to produce power,” Adam St. Pierre explains.

Any tips on how to move forward?

“Stand tall and run happy, that fixes most issues,” concludes coach Jason Koop.

LEARN 8 ESSENTIAL RUNNING FORM DRILLS

And the winners are…

Three of the most inspiring #howdoirun videos won Suunto Spartan Sport Wrist HR watches. Here are the winners.

Tim Larsson from Åre, Sweden

One last run before China. So, @suunto, how is my form? #suuntorun #howdoirun #xtrailadventurerace #xtrail #älskaåre

A post shared by Tim Larsson (@tmlarsson) on May 30, 2017 at 2:22am PDT

Tim Larsson comes from Åre, the mountain capital of Sweden. Coach Adam gave Tim mostly positive feedback, but pointed out an issue Tim was already aware of. “Due to weak hips I have a slight inward rotation on my left foot. This is something I have been working on and it feels good to get a confirmation,” says Tim.

“I have a small dream of running the entire Kungsleden (“The King’s Trail”), a 450-kilometer multiday trail run, here in Sweden in the end of the summer. So my focus now is simply on injury prevention so that I can go on for long periods. I am also trying to become a better, more efficient climber for the skimo season next winter.”

Aaron Harwood from Sydney, Australia

Filmed for the Suunto "How do I run" Contest on Sunday 11 June 2017. This was filmed by my awesome eight year old son. The time at the end is my finish time from the Sydney Morning Herald Half Marathon last month. I need some tips to run faster 😃. What a great morning. Thanks Suunto. #howdoirun #suunto #running #triathlon

A post shared by Aaron Harwood 🏊🏻🚴🏻🏃🏻 (@aaronbharwood) on Jun 10, 2017 at 10:04pm PDT

“Adam’s feedback has been really helpful. I was aware that I heel strike causing a deceleration at each stride. I was unaware of my posture and how that was making me overstride,” says Aaron Harwood from Sydney, Australia.

“As I run now I’m constantly thinking about maintaining an upright posture. I’ve noticed in the last few days that I’m now working other muscles as I can feel a difference during recovery. By reducing the tendency to overstride, I’m also able to maintain a quicker cadence. I will be adding high knee drills into my routine and I’m sure I’ll be able to start seeing my speed increase.”

To keep his motivation high, Aaron already has a goal in his mind “I’d like to run the New York marathon next year.”

Sarah Brough from Seattle, WA, USA

Posting this for the @suunto #howdoirun event ... I never really was an avid runner. Up until a year and a half ago, I couldn't even make it 1.5 miles. But, after having my second kid, I felt like I needed to improve my personal health and so, I started to run. Now, running has become an outlet for me, a way to challenge myself and see what my body can accomplish. There have been a lot of ups & downs, but through a lot of training, I've been able to accomplish goals that I never imagined I could, like running a full marathon & 2 half marathons. I've come to love the mental game, the runner's high and the sense of accomplishment I feel once I've beaten a PR. I want to keep improving which is why @suunto I'd love to know #howdoirun 🏃🏼 #suuntorun #suunto

A post shared by Sarah Brough (@sarbrough) on Jun 8, 2017 at 9:48pm PDT

“I've been able to work on coach Adam St. Pierre’s suggestions on a few runs already and honestly, it's been tough to change my stride. But, it feels a lot better when I do it. Also, I was able to go faster when I really focused on it, which is great because that's what I am most focused on right now in my training,” says Sarah Brough from Seattle, WA, USA

Sarah has set herself a goal to run two half marathons, with one of them being under two hours. “I just finished my first half in May & got a time of 2:05. My second one is in the end of August & I'm hoping to shave off those last 5 minutes, so I can reach my goal.”

Congratulations, Sarah, Tim and Aaron. And thank you everyone for submitting your videos Happy running!

Main image by Matt Trappe

READ AN INTRO TO DISTANCE RUNNING TECHNIQUE

Simon Donato takes on The Grouse Grind

The Grouse Grind is an iconic trail up the face of Grouse Mountain, overlooking Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. The trail is 2.9 kilometers long, with an elevation gain of 853 meters. Locals often refer to the trail as “Mother Nature’s Stairmaster.”

On Tuesday, June 20th Suunto Canada will be sponsoring the Suunto Multi-Grind Challenge. From dawn till dusk, racers will challenge each other to achieve the most Grouse Grind ascents in a one-day period. The current Multi-Grind Challenge record is 16 ascents! Or, over 13,500 meters of climbing!

What appealed to you about this race?

I’m attracted to this race because it’s got all the elements that I enjoy: Long day, vertical terrain, legendary route, and I know that I’ll get to face some mental battles along the way. The Grouse Grind is such an iconic route that one lap just doesn’t do it justice.

Any tips for tackling the Grouse Grind? There’s a lot of steps…

haha - Indeed. As with most really huge endurance challenges, this race will be won in the mind - not the legs. My goal is to keep the steps smooth and natural, not to push the pace too hard in the early stages, and try to keep it comfortable for as long as possible.

Have you ever done anything like this before?

I’ve never done a “stair climb” or “vertical” challenge per se, but I’ve put in many long days in the Canadian Rocky Mountains, both hiking and running for fun or chasing FKTs.

Any special strategies for tackling this much ascent in such a short time frame?

This race is unique because you get to rest on the descent by taking the Grouse Mountain Skyride, so trying to time things in such a way that you are not waiting for a tram car is critical. Eating, gear changes, etc., will all have to be done on the tram ride between ascents. One of the main goals is to climb at a very steady tempo - so that my splits are extremely similar lap - lap and avoid wasted time.

What will be your nutritional plan for the race?

My plan will be to take in as many calories as my body can handle - especially late in the race as that’s when I typically fade due to fatigue and a reduced desire to eat. Fatigue makes eating harder, and not eating enhances fatigue -it’s something I’ve struggled with in the past. In terms of calories - I’m going for as much real food as possible - and of course lots of Stoked Oats.

What performance metrics will you be focusing on during the race?

My biggest goal will be to maintain even splits…even if it feels painfully slow in the early stages. There is no benefit to reaching the summit after a hard push only to wait for the tram to arrive and take you back down.

Most importantly, the current record is 16 Grinds, how many do you think you can do?

Ha ha, the million dollar question. I would be happy with 14, and thrilled with 15.

What keeps you motivated during the climbs? How do you stay focused on the trail?

Motivation has always been about doing my best. It’s a question that I ask myself regularly during tough events and helps me push through the most difficult spots. In this case, I won’t be motivated by an absolute number, but more in maintaining a specific pace, and sticking to a well-designed nutrition plan.

How does your Suunto help you succeed in events like these?

I’ve always loved Suunto products - ever since I got into adventure racing in 1998. I think the bottom line is that I trust Suunto products - from watches to compasses and in a race where pacing is critical to success, having a watch (Suunto Spartan) that I trust gives me peace of mind. I know the watch will go as long as I do on the day and give me the metrics that I need to do my best - simple as that.

Any advice to newcomers of the Grind?

The Grind is an epic climb for many reasons, and tackling the Multi-Grind Challenge will move that needle well into the redzone. The most important elements to success in my opinion are setting goals (pacing, duration, etc.), managing nutrition, and adhering to a well thought out race plan. Really difficult events will challenge even the most hardened competitors and if there is no plan, or commitment to achieve a goal, then it’s always easier to throw in the towel when the going gets tough. Little things like appreciating the experience when you’re riding a high, to understanding that the lows don’t last forever will help pull athletes through this test!

Image of Simon Donato © Luis Moreira/Adventure ScienceGrouse Mountain images © Grouse Mountain

8 Essential running form drills

Improve your running technique with these essential running form drills – and follow them as a SuuntoPlus Guide on your watch!

UPDATED ON MARCH 29, 2022

In the previous weeks we have talked about running economy and given some key areas to focus on in your running technique . But how to actually change something or to improve? Here are XTERRA World Champion and professional coach Josiah Middaugh’s essential running drills for distance runners – with videos!

Follow these running form drills on your Suunto!

With the help of SuuntoPlus Guides, you can now follow these running form drills on your Suunto watch. Before starting a running exercise on your watch, go down to exercise options and select ’Running Form Drills’ from the SuuntoPlus Guides menu. Start the workout and you will see step-by-step guidance on one of your watch screens. Swipe left until you see it. Press lap (lower right button) to advance from one step to the next one.

Read on to learn the drills!

Skip with high knees (“A” skips)

Drive your knee up forcefully lifting you off the ground. Keep movements primarily in the sagittal plane. Keep your foot dorsiflexed, which means your toes drawn up towards your shin. This is a small skip since you land on the same foot and then switch. (Scroll down for a video of all the drills.)

Run with high knees

Similar to the “A” skips, but instead of skipping there is a quick transition from one foot to the other, just like running. Focus on breaking the vertical plane with your thigh each time.

“B” skips

This is just like the “A” skip, except after you drive the knee up, then extend the knee. Knee extension happens passively as you snap the leg back down with your glutes and hamstrings, pawing your foot to the ground.

Butt kicks (heel to butt)

Traditional butt kicks are usually performed incorrectly, swinging the heel in a half circle towards the butt. Instead, draw the keep up in a straight line towards the bottom of the butt or top of the hamstrings. To do this, allow the knee to come forward, but not quite as high as the high knees drill.

Power skips

This has all of the same points as the “A” skips except you are going for more height. Momentum is created by driving the knee up and also forcefully pushing off the ground.

Carioca drill

Most running is performed in the sagittal plane, but stabilizing also occurs in the frontal plane. The carioca drill is a side ways motion requiring adduction/abduction and coordination. Face sideways and cross your trailing leg in front and then behind and you continue in the sideways direction. Continue facing the same direction for your return trip.

Bounding

Bounding is a higher intensity running drill designed to improve power and efficiency. Essentially bounding is just an exaggerated run with lots of vertical and horizontal displacement. Go for both height and distance with each stride. To keep from skipping, try jogging 5-10 yards before starting the drill. These can be performed on flat ground or uphill.

Strides

Strides are just controlled sprints. Gradually increase speed for 30-40 meters and then maintain high speed with good, controlled form for another 40-60 meters. The key is not to strain or sprint all out. Make it look easy. I like 70-100 meters for these on a relatively soft surface such as a rubberized track or turf.

Watch all the running form drills on video!

Watch coach Josiah's essential running form drills here.

Josiah Middaugh is a XTERRA Pan America Champion and 2015 XTERRA World Champion. He has a master’s degree in kinesiology and has been a certified personal trainer for over 15 years (NSCA-CSCS).

Images and video by Matt Trappe